Maybe you’ve learned that people with psychopathy have an underactive amygdala, the so-called “fear center” of the brain. Do the data support that claim? Not really, according to my new review with Mickela Heilicher and Mike Koenigs.

People with psychopathy are notorious for their deceitful interpersonal style, callousness towards others, recklessness, and frequent criminal behavior. Some of the most influential theories in the field make this basic hypothesis: people with psychopathy have lower activity than most people in their amygdala – two small regions buried deep in the left and right sides of the brain – and as a result they have difficulty feeling fear of punishment and understanding when other people are in distress.

This was a reasonable hypothesis when it was first published 20-30 years ago. Since then, scientists have conducted over 100 studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to put this hypothesis to the test.

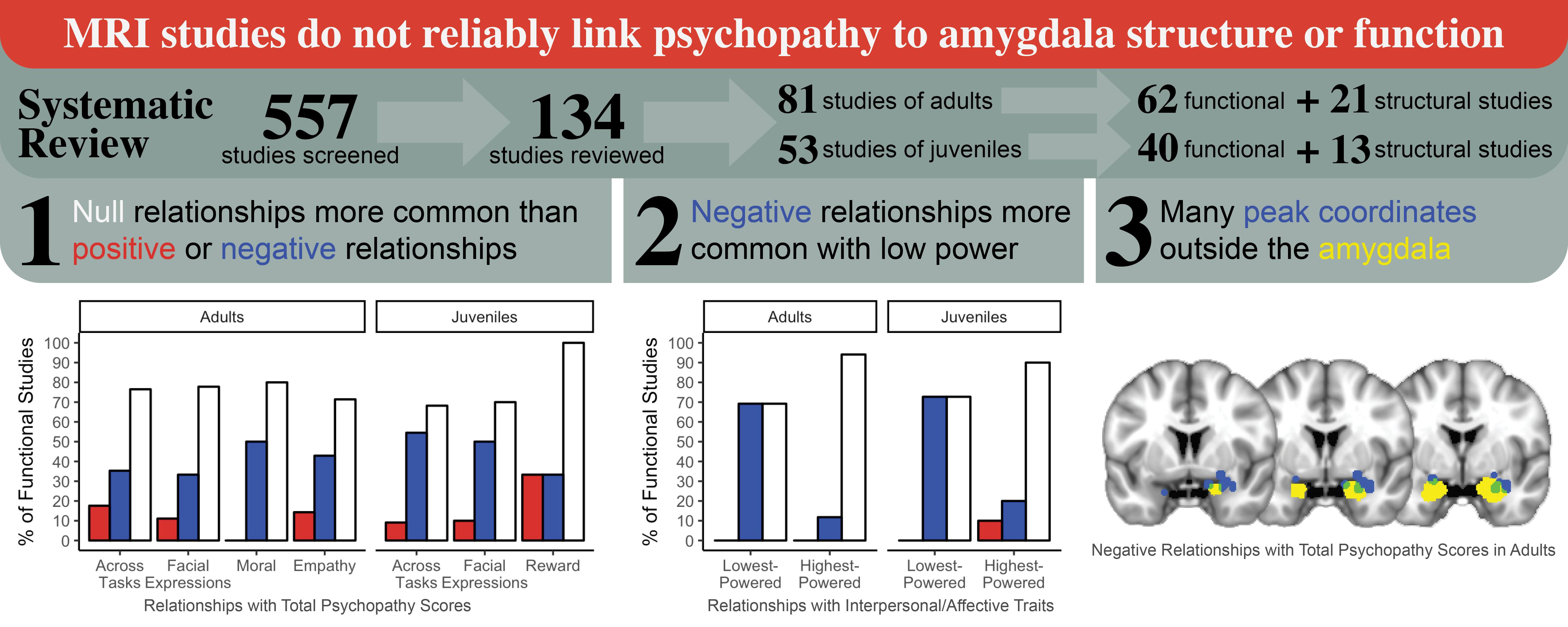

We reviewed 134 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of psychopathy to see if the data actually supported the amygdala hypothesis. We reviewed studies that tested adults (18 years of age and older) as well as studies that tested juveniles (younger than 18). Most of the studies (102) measured amygdala activity – basically, how much blood was flowing to the amygdala while the participant performed a task set by the experimenter. But some of the studies measured the size of the amygdala. So we were able to review evidence about amygdala function (activity) and structure (size).

There were three main takeaways from our study.

First main takeaway: Most studies found at least one null relationship. That means, most studies had at least one experimental context in which amygdala activity was essentially the same for people with psychopathy and relatively healthy people.

Why might that be? We explored some possible explanations.

It’s possible that reduced amygdala activity may depend on context. However, if that’s true, then the existing MRI studies do not capture the context(s) in which people with psychopathy show reduced amygdala activity. To be clear, those contexts included times when participants were trying to understand another person’s emotions based on their facial movements, times when participants were trying to determine the morality of a scenario, and times when they were doing a fear learning task (learning to associate something non-threatening with a threat like an electric shock). Across all these contexts, people with psychopathy tended to have similar amygdala activity to relatively healthy people.

Alternatively, methodological limitations may have prevented studies from observing reduced amygdala activity. One common limitation of MRI studies is low power due to small sample size. Low power means a study has a lower chance of observing a relationship that exists. On the flip side, low power also inflates the significance of observed relationships.

This leads us to our

Second main takeaway: Studies with low power (small sample size) were more likely to observe reduced amygdala activity among people with psychopathy. For example, the lowest-powered studies of juveniles were more than 3 times likelier to find reduced activity related to psychopathic traits than high-powered studies.

We’re not exactly sure why the lowest-powered studies were more likely to find reduced amygdala activity. But I’ll give one possibility here. It’s possible that some scientists conducted studies with low power (for example, collecting data from only 10 subjects), analyzed the data, were unable to find the expected relationship between psychopathy and amygdala activity, and decided not to publish their findings because their study had low power. They may thought, “we cannot be confident about this null finding, because we may have had too few participants to actually find a relationship that exists.” This is known as the ‘file drawer problem,’ meaning scientists file away their studies without publishing them because the study did not produce interesting or ‘significant’ results. This may have decreased the number of null findings among low-powered studies, making the proportion of reduced-amygdala findings seem relatively higher.

At this point, you may be wondering: What about the studies that did find reduced amygdala activity in psychopathy? What can we learn from those studies, for example about where in the amygdala the reduced activity is occurring? To answer this, we pulled peak coordinates from these studies.

For background, when a study finds a region with reduced (or increased) activity, the study should (and many do) report the 3D coordinates of the spot in the region where the difference was greatest (the “peak coordinates”). This helps other researchers find that spot exactly and compare across studies.

This led us to our

Third main takeaway: Many peak coordinates did not fall within the amygdala. To be clear, these were peak coordinates of regions that were labeled “amygdala” in the original paper. So even those studies that did claim to find reduced amygdala activity may have actually found reduced activity in regions nearby the amygdala, rather than within the amygdala.

Why might that be? There are a few possible explanations.

Imprecise labeling may have inflated the sense that psychopathy is related to reduced amygdala activity. To address this, we have recommended that researchers should compare their results to a brain atlas (which maps out the boundaries between regions) and report doing so.

It’s also possible that, in the original data, the region that showed reduced activity did include the amygdala, even though the peak coordinate was outside the amygdala. But if amygdala is a key region of dysfunction in psychopathy, as some theories suggest, I would expect most studies to find peak coordinates within the amygdala. That is not the case.

To sum up, 20-30 years after the amygdala hypothesis of psychopathy was published, the results are in, and there is little evidence supporting the hypothesis. Most studies have found a null relationship between psychopathy and amygdala activity (or volume). Many studies that did find a relationship 1) had low power, and/or 2) reported peak coordinates outside the amygdala.

Lastly, I’ll point out that, in general, the notion of the amygdala as the brain’s “fear center” is changing. The amygdala is not necessary for fear and may not be involved in human fear conditioning. In fact, the search for a “fear center” in the brain is likely misguided.

It would likely be more fruitful to study large-scale brain networks that support core brain functions, rather than specific brain regions like the amygdala, as a way of understanding the brain basis of psychopathy (and other forms of mental illness). Read more about these large-scale brain networks in my other Research Explained posts.

You can read the full paper here.

Deming, P., Heilicher, M., & Koenigs, M. (2022). How reliable are amygdala findings in psychopathy? A systematic literature review of MRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 142, 104875.